Self-directed learning: A fundamental competence in a rapidly changing world

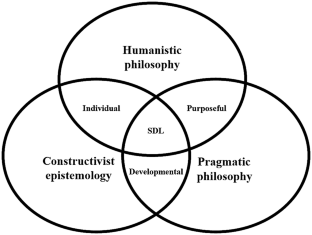

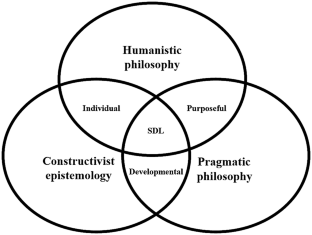

Self-directed learning is a fundamental competence for adults living in our modern world, where social contextual conditions are changing rapidly, especially in a digital age. The purpose of the present article is to review key issues concerning self-directed learning in terms of (1) what are the historical foundations of the self-directed learning concept?; (2) who may benefit from self-directed learning?; (3) who is likely to carry it out?; and (4) what does research show regarding outcomes of the self-directed learning process? The author takes into consideration humanistic philosophy, pragmatic philosophy and constructivist epistemology, which together concern a process of learning that is individual, purposeful and developmental. Potentially everyone can benefit from self-directed learning competence, but both societal and individual factors may influence whether self-directed learning is likely to be carried out. The author discusses a number of empirical studies that examine outcomes of the self-directed learning process in informal/non-formal online contexts and in formal educational settings. Research findings highlight the importance of realising the opportunity to foster learners’ self-directed learning competence in formal educational settings.

Résumé

L’auto-apprentissage, une compétence indispensable dans un monde en rapide mutation – L’apprentissage auto-dirigé est une compétence décisive pour les adultes de notre monde moderne, où les contextes sociaux évoluent constamment, en particulier à l’ère du numérique. Le présent article poursuit le but de recenser les grandes questions sur l’apprentissage auto-dirigé : 1) Quelles sont les bases historiques du concept d’auto-apprentissage ? 2) Qui peut tirer profit de l’auto-apprentissage ? 3) Qui est susceptible de l’accomplir ? 4) Que révèle la recherche sur les résultats de la démarche d’auto-apprentissage ? L’auteur prend en considération la philosophie humaniste, la philosophie pragmatique et l’épistémologie constructiviste, qui ensemble affectent une démarche d’apprentissage individuelle, intentionnelle et évolutive. Toute personne peut potentiellement tirer profit de la compétence en auto-apprentissage, mais des facteurs individuels et sociétaux peuvent influencer la probabilité que l’auto-apprentissage soit accompli. L’auteur analyse plusieurs études empiriques qui examinent les résultats de la démarche d’auto-apprentissage, à la fois dans des contextes en ligne non formels et informels et dans des cadres éducatifs formels. Les résultats scientifiques signalent l’importance de créer des opportunités de stimuler la compétence en auto-apprentissage dans les cadres éducatifs formels.

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this article

Subscribe and save

Springer+ Basic

€32.70 /Month

- Get 10 units per month

- Download Article/Chapter or eBook

- 1 Unit = 1 Article or 1 Chapter

- Cancel anytime

Buy Now

Price includes VAT (France)

Instant access to the full article PDF.

Rent this article via DeepDyve

Similar content being viewed by others

Self-determined Learning (Heutagogy) and Digital Media Creating integrated Educational Environments for Developing Lifelong Learning Skills

Chapter © 2018

Self-Directed Learning at School and in Higher Education in Africa

Chapter © 2021

Learners Self-directing Learning in FutureLearn MOOCs: A Learner-Centered Study

Chapter © 2019

Explore related subjects

Notes

In a nutshell, behaviourism is a theory of human learning. A learning process regarded through a behaviourist lens is characterised by predictable, measurable and pre-definable learning outcomes for all learners (Murtonen et al. 2017). From a behaviourist perspective, the ultimate learning objective of a learning process is to control learners’ behaviour – to shape their growth in a particular direction (Bruner 1966; Skinner 1987 [1971]; Thorndike 1898; Watson 1913). Thus, the process benefits from learners acting meekly and uncritically rather than actively or judgmentally (Dewey 2013 [1916]).

Constructivism also represents a theoretical approach to understanding the nature of knowledge. It refers to a learner’s experience of discovering how elements of knowledge are “constructed” and how they are connected to other elements. A learning process regarded through a constructivist lens concerns learning in which an inquiry project drives the learning process, where active and judgemental (critical) thinking is fundamental in facilitating successful learning: a process that represents learners solving or resolving authentic real-world-based problems (Jonassen 1999; Morris 2019a).

Humanistic philosophy in an educational context concerns a developmental process of learning in which emphasis is placed on facilitating desirable and responsible personal learner growth towards learner self-actualisation (Elias and Merriam 1995; Groen and Kawalilak 2014). Pragmatic philosophy concerns the importance of testing theoretical concepts in real-world contexts to assess their effectiveness, which is viewed as necessary to secure deep understanding (see Morris 2019c for a further discussion of experiential learning theory, which is founded on pragmatism).

Epistemology refers to the theory of knowledge (see footnote 2 above for an explanation of constructivism).

According to the Council of Europe, “informal learning takes place outside schools and colleges and arises from the learner’s involvement in activities that are not undertaken with a learning purpose in mind. Informal learning is involuntary and an inescapable part of daily life; for that reason, it is sometimes called experiential learning.” (CoE n.d., para. 3, italics in original).

Further Education (FE) refers to any study after secondary education that is not part of higher education (i.e. not part of an undergraduate or graduate degree). In England, overwhelmingly the most common qualifications undertaken in Further Education colleges are various vocational education and training certificates by 16- to 18-year-old learners (see Morris 2018b).

“Numerous studies have verified the factor structure and construct validity of the Big Five constructs (Openness, Conscientiousness, Extroversion, Agreeableness, and Neuroticism; Costa and McCrae, 1994). The five-factor model suggests that there are five independent factors of personality most commonly labeled: Openness, Conscientiousness, Extroversion, Agreeableness, and Neuroticism (often referred to by the acronym OCEAN)” (Kirwan et al. 2014, p. 3).

Narrow traits are defined as “either subscales of the Big Five or as traits not encompassed by the Big Five model” (Kirwan et al. 2010, p. 22), such as Sense of Identity, Optimism, Tough-Mindedness and Work Drive (see Kirwan et al. 2010).

The Oddi Continuing Learning Inventory (OCLI) is a 24-item instrument developed by Lorys Oddi to identify self-directed continuing learners by considering their personality characteristics. The Self-Directed Learning Readiness Scale (SDLRS) “is a self-report questionnaire with Likert-type items developed by Dr. Lucy M. Guglielmino in 1977. It is designed to measure the complex of attitudes, skills, and characteristics that comprise an individual’s current level of readiness to manage his or her own learning” (http://www.lpasdlrs.com/ [accessed 13 June 2019]). The Personal Responsibility Orientation to Self-Direction in Learning Scale (PRO-SDLS) aims to “measure self-directedness in learning among college students based on an operationalisation of the personal responsibility orientation (PRO) model of self-direction in learning” (Stockdale and Brockett 2011, p. 161).

Knowledge gap theory concerns “the increase of information in society [that] leads to differing reception dependent on socioeconomic status” (Rohs and Ganz 2015, p. 3, in reference to the work of Tichenor et al. 1970).

Systemic-constructivism, which builds on the concept of constructivism (see footnote 2 above) concerns a theoretical perspective on learning and the process of meaning-making (knowledge construction), which posits that a “learner’s personal understanding of the world and how they interpret new experiences, and make meaning of the world in which they live, is determined by their unique set of experiences and interpretations of themselves and their world since birth. Meaning-making is always an individual and personal, unique, process. However, in addition, a key consideration is that experience and learning never occurs in a social or contextual vacuum” (Morris 2019b, p. 304).

Rather than being concerned with what information we have learned (what we know), constructive-developmental theory highlights that appreciating our way of knowing is essential. Kegan’s (2009) constructive-developmental theory proposes that over time the ways in which we understand and construct experience can become more complex.

References

- Alharbi, H. A. (2018). Readiness for self-directed learning: How bridging and traditional nursing students differs? Nurse Education Today,61, 231–234. ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Arnold, R. (2015). How to teach without instructing: 29 smart rules for educators. Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield. Google Scholar

- Arnold, R. (2017). The power of personal mastery: Continual improvement for school leaders and students. Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield. Google Scholar

- Bagnall, R. G., & Hodge, S. (2018). Contemporary adult and lifelong education and learning: An epistemological analysis. In M. Milana, S. Webb, J. Holford, R. Walker, & P. Jarvis (Eds.), Palgrave international handbook on adult and lifelong education and learning (pp. 13–34). Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan. ChapterGoogle Scholar

- Barnes, M. E. (2016). The student as teacher educator in service-learning. Journal of Experiential Education,39(3), 238–253. ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Barry, M., & Egan, A. (2018). An adult learner’s learning style should inform but not limit educational choices. International Review of Education,64(1), 31–42. ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Beach, P. (2017). Self-directed online learning: A theoretical model for understanding elementary teachers’ online learning experiences. Teaching and Teacher Education,61, 60–72. ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Beckers, J., Dolmans, D., & van Merriënboer, J. (2016). e-Portfolios enhancing students’ self-directed learning: A systematic review of influencing factors. Australasian Journal of Educational Technology,32(2), 32–46. Google Scholar

- Beckers, J., Dolmans, D. H., Knapen, M. M., & van Merriënboer, J. J. (2018). Walking the tightrope with an e-portfolio: Imbalance between support and autonomy hampers self-directed learning. Journal of Vocational Education & Training,71(2), 260–288. ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Bonk, C. J., Lee, M. M., Kou, X., Xu, S., & Sheu, F. R. (2015). Understanding the self-directed online learning preferences, goals, achievements, and challenges of MIT OpenCourseWare subscribers. Journal of Educational Technology & Society,18(2), 349–368. Google Scholar

- Bonk, C. J., Zhu, M., Kim, M., Xu, S., Sabir, N., & Sari, A. R. (2018). Pushing toward a more personalized MOOC: Exploring instructor selected activities, resources, and technologies for MOOC design and implementation. International Review of Research in Open and Distributed Learning,19(4), 92–115. ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Boyer, S. L., Edmondson, D. R., Artis, A. B., & Fleming, D. (2014). Self-directed learning: A tool for lifelong learning. Journal of Marketing Education,36(1), 20–32. ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Brookfield, S. D. (1986). Understanding and facilitating adult learning: A comprehensive analysis of principles and effective practices. Buckingham: McGraw-Hill. Google Scholar

- Bruner, J. S. (1966). Toward a theory of instruction. Cambridge, MA: Belknap/Harvard University Press. Google Scholar

- CoE (Council of Europe) (n.d.). Key terms: Formal, non-formal and informal learning [webpage]. Strasbourg: Council of Europe. Retrieved 17 June 2019 from https://www.coe.int/en/web/lang-migrants/formal-non-formal-and-informal-learning.

- Costa, P., & McCrae, R. (1994). Stability and change in personality from adolescence through adulthood. In C. F. Halverson, G. A. Kohnstamm, & R. P. Martin (Eds.), The developing structure of temperament and personality from infancy to adulthood (pp. 139–155). Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum. Google Scholar

- Davis, M. (2012). A plea for judgment. Science and Engineering Ethics,18(4), 789–808. ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Dewey, J. (1908). What does pragmatism mean by practical? The Journal of Philosophy, Psychology and Scientific Methods,5(4), 85–99. ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Dewey, J. (2010 [1915/1902]). The school and society [1915] and The child and the curriculum [1902]. Chicago, IL: The University of Chicago Press.

- Dewey, J. (2013 [1916]). Essays in experimental logic. Mineola, NY: Dover Publications.

- Duffy, G., & Bowe, B. (2010). A strategy for the development of lifelong learning and personal skills throughout an undergraduate engineering programme. Paper presented at the IEEE Conference “Transforming engineering education: Creating interdisciplinary skills for complex global environments”, held in Dublin, Ireland 6–9 April 2010. https://doi.org/10.1109/tee.2010.5508842.

- Dunlap, J. C., & Grabinger, S. (2003). Preparing students for lifelong learning: A review of instructional features and teaching methodologies. Performance Improvement Quarterly,16(2), 6–25. ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Elias, J. L., & Merriam, S. B. (1995). Philosophical foundations of adult education. Melbourne, FL: Krieger Publishing. Google Scholar

- Garrison, D. R. (1997). Self-directed learning: Toward a comprehensive model. Adult Education Quarterly,48(1), 18–33. ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Gibbons, M. (2002). The self-directed learning handbook: Challenging adolescent students to excel. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass. Google Scholar

- Groen, J., & Kawalilak, C. (2014). Pathways of adult learning: Professional and education narratives. Toronto, ON: Canadian Scholars’ Press. Google Scholar

- Grow, G. O. (1991). Teaching learners to be self-directed. Adult Education Quarterly,41(3), 125–149. ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Guglielmino, L. M. (1978). Development of the self-directed learning readiness scale. Doctoral dissertation, University of Georgia, 1977. Dissertation Abstracts International, 38, 6467A.

- Henschke, J. (2016). A history of andragogy and its documents as they pertain to adult basic and literacy education. PAACE Journal of Lifelong Learning,25, 1–28. Google Scholar

- Hiemstra, R., & Brockett, R. G. (2012). Reframing the meaning of self-directed learning: An updated model. Paper presented at the 54th Annual Adult Education Research Conference (AERC), held in Saratoga Springs, NY 1–3 June 2012. In Proceedings of the 54th Annual Adult Education Research Conference (pp. 155–161). Manhattan, KS: New Prairie Press. Retrieved 30 May 2019 from https://newprairiepress.org/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=3070&context=aerc.

- Hoffman, R. R., Ward, P., Feltovich, P. J., DiBello, L., Fiore, S. M., & Andrews, D. (2014). Accelerated expertise: Training for high proficiency in a complex world. New York, NY: Psychology Press. Google Scholar

- Jonassen, D. H. (1999). Designing constructivist learning environments. In C. M. Reigeluth (Ed.), Instructional-design theories and models: A new paradigm of instructional theory (Vol. II, pp. 215–239). Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum. Google Scholar

- Jones, J. A. (2017). Scaffolding self-regulated learning through student-generated quizzes. Active Learning in Higher Education. https://doi.org/10.1177/1469787417735610. ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Jossberger, H., Brand-Gruwel, S., Boshuizen, H., & Van de Wiel, M. (2010). The challenge of self-directed and self-regulated learning in vocational education: A theoretical analysis and synthesis of requirements. Journal of Vocational Education & Training,62(4), 415–440. ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Jossberger, H., Brand-Gruwel, S., van de Wiel, M. W., & Boshuizen, H. (2017). Learning in workplace simulations in vocational education: A student perspective. Vocations & Learning,11(2), 179–204. ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Kegan, R. (2009). What “form” transforms? A constructive-developmental approach to transformative learning. In K. Illeris (Ed.), Contemporary theories of learning: Learning theorists in their own words (pp. 35–54). Abingdon: Routledge. Google Scholar

- Kicken, W. S., Brand-Gruwel, S., van Merrienboer, J. J., & Slot, W. (2009). The effects of portfolio-based advice on the development of self-directed learning skills in secondary vocational education. Educational Technology Research & Development,57(4), 439–460. ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Kirwan, J. R., Lounsbury, J. W., & Gibson, L. W. (2010). Self-directed learning and personality: The Big Five and narrow personality traits in relation to learner self-direction. International Journal of Self-Directed Learning,7(2), 21–34. Google Scholar

- Kirwan, J. R., Lounsbury, J. W., & Gibson, L. W. (2014). An examination of learner self-direction in relation to the Big Five and narrow personality traits. SAGE Open,4(2), 1–14. ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Knowles, M. S. (1970). The modern practice of adult education: Andragogy versus pedagogy. New York: New York Association Press. Google Scholar

- Knowles, M. S. (1975). Self-directed learning: A guide for learners and teachers. Chicago, IL: Follett. Google Scholar

- Knowles, M. S. (1980). The modern practice of adult education: From pedagogy to andragogy (revised and updated). New York: Cambridge Adult Education. Google Scholar

- Knowles, M. S. (2001). Contributions of Malcolm Knowles. In K. O. Gangel & J. C. Wilhoit (Eds.), The Christian handbook on adult education (pp. 91–103). Grand Rapids, MI: Baker Books. Google Scholar

- Kranzow, J., & Hyland, N. (2016). Self-directed learning: Developing readiness in graduate students. International Journal of Self-Directed Learning,13(2), 1–14. Google Scholar

- Leach, N. (2018). Impactful learning environments: A humanistic approach to fostering adolescents’ postindustrial social skills. Journal of Humanistic Psychology. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022167818779948. ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Lindeman, E. C. (1926). The meaning of adult education. New York: New Republic. Google Scholar

- Lounsbury, J., Levy, J., Park, S., Gibson, L., & Smith, R. (2009). An investigation of the construct validity of the personality trait of self-directed learning. Learning and Individual Differences,19(4), 411–418. ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Louws, M. L., Meirink, J. A., van Veen, K., & van Driel, J. H. (2017). Teachers’ self-directed learning and teaching experience: What, how, and why teachers want to learn. Teaching and Teacher Education,66, 171–183. ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Ma, X., Yang, Y., Wang, X., & Zang, Y. (2018). An integrative review: Developing and measuring creativity in nursing. Nurse Education Today,62, 1–8. ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Major, D. A., Turner, J. E., & Fletcher, T. D. (2006). Linking proactive personality and the Big Five to motivation to learn and development activity. Journal of Applied Psychology,91(4), 927–935. ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Merriam, S. B. (2018). Adult learning theory: Evolution and future directions. In K. Illeris (Ed.), Contemporary theories of learning (pp. 83–96). New York: Routledge. ChapterGoogle Scholar

- Merriam, S. B., Caffarella, R. S., & Baumgartner, L. M. (2007). Learning in adulthood: A comprehensive guide. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass. Google Scholar

- Mocker, D. W., & Spear, G. E. (1982). Lifelong learning: Formal, nonformal, informal and self-directed. Information Series No. 241. Columbus, OH: ERIC Clearinghouse on Adult, Career, and Vocational Education/National Center for Research in Vocational Education/Ohio State University. Retrieved 30 May 2019 from http://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED220723.pdf.

- Moore, M. G. (1972). Learner autonomy: The second dimension of independent learning. Convergence,5(2), 76–88. Google Scholar

- Morris, T. H. (2018a). Book review. How to teach without instructing: 29 smart rules for educators, by R. Arnold. Adult Education Quarterly,68(1), 80–81. ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Morris, T. H. (2018b). Vocational education of young adults in England: A systemic analysis of teaching–learning transactions that facilitate self-directed learning. Journal of Vocational Education & Training,70(4), 619–643. Google Scholar

- Morris, T. H. (2019a). Adaptivity through self-directed learning to meet the challenges of our ever-changing world. Adult Learning,30(1), 56–66. ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Morris, T. H. (2019b). An analysis of Rolf Arnold’s systemic-constructivist perspective on self-directed learning. In M. Rohs, M. Schiefner-Rohs, I. Schüßler, & H.-J. Müller (Eds.), Educational perspectives on transformations and change processes (pp. 301–313). Bielefeld: WBV Verlag. Google Scholar

- Morris, T. H. (2019c). Experiential learning: A systematic review and revision of Kolb’s model. Interactive Learning Environments. https://doi.org/10.1080/10494820.2019.1570279. ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Morrison, D., & Premkumar, K. (2014). Practical strategies to promote self-directed learning in the medical curriculum. International Journal of Self-Directed Learning,11(1), 1–12. Google Scholar

- Murtonen, M., Gruber, H., & Lehtinen, E. (2017). The return of behaviourist epistemology: A review of learning outcomes studies. Educational Research Review,22, 114–128. ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Nasri, N. M. (2017). Self-directed learning through the eyes of teacher educators. Kasetsart Journal of Social Sciences. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.kjss.2017.08.006. ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Oddi, L. F. (1986). Development and validation of an instrument to identify self-directed continuing learners. Adult Education Quarterly,36(2), 97–107. ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Onah, D. F., Sinclair, J., & Boyatt, R. (2014). Dropout rates of massive open online courses: Behavioural patterns. Paper presented at the 6th International Conference on Education and New Learning Technologies, held in Barcelona, Spain 7–9 July 2014. In EDULEARN14 proceedings (pp. 5825–5834). Valencia: International Academy of Technology, Education and Development (IATED).

- Pintrich, P. R. (2004). A conceptual framework for assessing motivation and self-regulated learning in college students. Educational Psychology Review,16(4), 385–407. ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Rogers, C. R. (1969). Freedom to learn. Columbus, OH: Charles Merrill. Google Scholar

- Rohs, M., & Ganz, M. (2015). MOOCs and the claim of education for all: A disillusion by empirical data. The International Review of Research in Open and Distributed Learning,16(6), 1–19. ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Sawatsky, A. P., Ratelle, J. T., Bonnes, S. L., Egginton, J. S., & Beckman, T. J. (2017). A model of self-directed learning in internal medicine residency: A qualitative study using grounded theory. BMC Medical Education,17, Art. 227. ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Schmidt-Hertha, B., & Rohs, M. (2018). Medienpädagogik und erwachsenenbildung [Media education and adult education]. Medien Pädagogik: Zeitschrift für Theorie und Praxis der Medienbildung,30, 1–8. Google Scholar

- Seibert, S. E., Kraimer, M. L., & Crant, J. M. (2001). What do proactive people do? A longitudinal model linking proactive personality and career success. Personnel Psychology,54(4), 845–874. ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Skinner, B. F. (1987 [1971]). Beyond freedom and dignity. New York: Bantam Books.

- Stockdale, S. L., & Brockett, R. G. (2011). Development of the PRO-SDLS: A measure of self-direction in learning based on the personal responsibility orientation model. Adult Education Quarterly,61(2), 161–180. ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Tan, C. (2017). A Confucian perspective of self-cultivation in learning: Its implications for self-directed learning. Journal of Adult and Continuing Education,23(2), 250–262. ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Tough, A. M. (1971). The adults’ learning projects: A fresh approach to theory and practice in adult education. Toronto, ON: The Ontario Institute for Studies in Education. Retrieved 30 May 2019 from http://ieti.org/tough/books/alp.htm.

- Thorndike, E. L. (1898). Animal intelligence: An experimental study of the associative processes in animals. The Psychological Review, Monograph Supplements,2(4), i-09. Google Scholar

- Tichenor, P. J., Donohue, G. A., & Olien, C. N. (1970). Mass media flow and differential growth in knowledge. Public Opinion Quarterly,34(2), 159–170. ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Ward, P., Gore, J., Hutton, R., Conway, G. E., & Hoffman, R. R. (2018). Adaptive skill as the conditio sine qua non of expertise. Journal of Applied Research in Memory and Cognition,7(1), 35–50. ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Watson, J. (1913). Psychology as the behaviorist views it. Psychological Review,20(2), 158–177. ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Zimmerman, B. J. (1990). Self-regulated learning and academic achievement: An overview. Educational Psychologist,25(1), 3–17. ArticleGoogle Scholar

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author.